Challenges

Naturally, the special regional pride of the Inner Salzkammergut also becomes apparent in matters of architectural heritage: “For 7,500 years, we have built Hallstatt ourselves, until it became World Heritage, and since then, people from outside keep coming to tell us how to do it.” This criticism has some foundation. In fact, the region has largely been spared from major or minor architectural missteps. When locals build new houses or renovate old ones, there is a common sense to follow the traditional style and use regional materials. This also applies to areas that are not as culturally prominent as Hallstatt, such as Obertraun.

For Hallstatt, the current actors are considered well-acquainted with the specificities of the town. Therefore, the establishment of a local advisory board is not currently being discussed—there is concern that members unfamiliar with Hallstatt’s particularities could join, that advice could become one-dimensional, and that discussion within a board could reduce the overall quality of guidance compared to the current system.

At present, a heritage ensemble protection under the Monuments Protection Act is not an issue in Hallstatt. This also affects other possible instruments related to the assessment of private property.

Many listed and heritage-worthy buildings in Hallstatt are under considerable pressure for modifications, particularly in attics (raising roofs, adding skylights). A noted problem is that enlarging windows in listed buildings to allow more light is often difficult.

A central question for the future of architectural heritage in the World Heritage region is whether the described common sense will continue to be passed down among the population, or whether the attitude of private builders—similar to other World Heritage cultural landscapes—might eventually change.

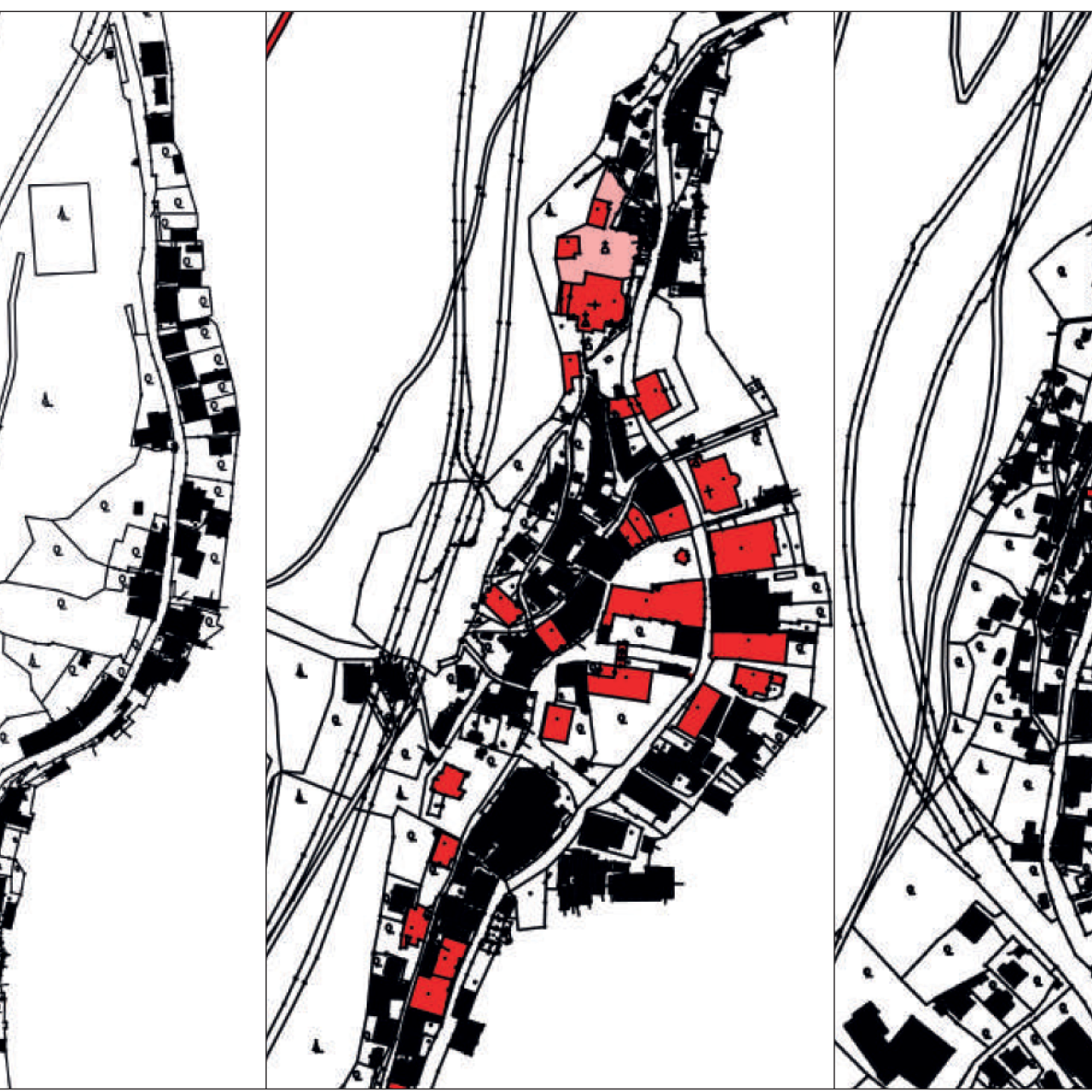

Experts are generally supportive of more binding regulations. For example, the BDA views positively the adaptation of the “Wachau Zones” model developed in Lower Austria and applied in the Wachau World Heritage Site. This involves specialized zoning plans that set clear rules for individual buildings based on their significance to the townscape.

The creation of a new integrated funding model to support architectural heritage and landscape management should at least be considered. The local population has directly benefited from World Heritage status in this way, and positive examples for maintaining traditional architectural heritage have continuously been created. If a new model were to be developed, it would be essential to evaluate existing funding models for their strengths and weaknesses, discuss future content and management of funding systematically, and define their spatial scope.

Such a model could be based on the Salzburg Historic Town Preservation Act, which consists of a clear legal foundation (a state law), an expert commission (two representatives from the city, two from the state, and one from the BDA), and the Historic Town Preservation Fund as a funding instrument. The difference would be that the zoning plans (equivalent to the legal regulation) could define the handling of individual plots and buildings more clearly than in the Salzburg law. The requirement to submit all regulated construction projects in the World Heritage area to the expert commission (§12 para.1 Sbg Historic Town Preservation Act) could be removed in these zoning plans.

Introducing zoning plans has two advantages: first, the conditions for builders and planners are defined more clearly from the start; second, decision-making on architectural heritage matters is elevated to a broader level (the municipal council). The Upper Austrian Spatial Planning Act even allows, in particularly difficult cases, a completely textual zoning plan without graphical representation—tailored for towns like Hallstatt.

There is significant potential in further research and communication on the benefits of traditional building techniques, including climate and environmental aspects. For example, expert opinion holds that wooden sash windows produce fewer thermal bridges than plastic windows. Limestone walls with lime mortar have a cooling effect. Increased use of peat could also contribute to revitalizing moors, which hold untapped climate potential. Another untapped potential is a deeper consideration of centuries-old adapted construction techniques in alpine buildings. The existing awareness of traditions in intangible cultural heritage could be more strongly linked with architectural heritage. The HTBLA provides a local competence center for this purpose.

An important model project could be the handling of larger buildings, such as the administrative building on the southern edge of Hallstatt. A discussion on advertising guidelines for Hallstatt’s town center is also suggested. Such guidelines already exist in several district capitals in Upper Austria, including Steyr, Wels, Braunau, Schärding, Freistadt, and Vöcklabruck.

The most extensive nature protection designation in the Upper Austrian part of the World Heritage Site is the Dachstein Nature Reserve, located within the municipalities of Hallstatt, Gosau, and Obertraun, which partially coincides with the eponymous European protected area.

In addition, the Große and Kleine Löckenmoos in Gosau are designated as nature reserves. Within the World Heritage area, there are also 12 natural monuments—mostly caves, karst springs, and individual trees—as well as nearly 25 so-called “eco-areas,” which are recognized for their high ecological value but are not yet legally protected. Most of these sites are wetlands, moors, or scree slopes. Larger areas in this category include the wetland on the southern shore of Lake Hallstatt, parts of the Koppenwinkel in Obertraun, the Gosaulacke (both at least partly within the Dachstein Nature Reserve), part of the Echerntal in Hallstatt, the Gjaidalm (within the Dachstein European protected area), and the Dammwiese in the Hallstatt high valley, an archaeologically important site with a prehistoric settlement.

Another site of conservation interest is the “Uferwiesen Steeg,” a wetland on the northern shore of Lake Hallstatt in the municipality of Bad Goisern, directly adjacent to the World Heritage area. Its potential integration into the World Heritage zone would be logical, as the current boundary along the lakeshore is not entirely clear.

Another important protection measure is the lakeshore protection zone of Lake Hallstatt, extending 500 meters from the shore. It covers the entire settlement area of the core zone of Bad Goisern, the historic market of Hallstatt, about half of the Echerntal settlement, and peripheral areas of Obertraun. Exception regulations exist for all lakeshore protection zones in Upper Austria; the regulation for Lake Hallstatt was updated in 2020 following an amendment to the Nature Conservation Act, now only applying to activities requiring authorization. Previously, all interventions were generally prohibited.

On the Styrian side, the core zone coincides with the strict protection zone (Zone A) of Nature Reserve XVIII, the “Styrian Dachstein Plateau.” The southernmost extension covers the Notgasse and Riesgasse on the municipality of Gröbming, a culturally valuable segment of an old mountain path from Obertraun to the Enns Valley, located in a rock hollow. The area is protected both as a natural monument and a heritage object.

The Styrian Dachstein Plateau Nature Reserve largely overlaps with the corresponding European protected area (FFH Directive). The bird protection area in the same region is even slightly larger.

Tourism in the protected areas requires careful management. The Krippenstein mountain experience has been significantly enhanced in recent years through the construction of the Five Fingers platform and other facilities around the cable car mountain station. Passenger numbers increased from 32,000 to 180,000 over 15 years. Summer surpluses are invested in the presentation of middle and upper stations, such as the caves. The Five Fingers has replaced the show caves at the middle station in terms of visitor numbers and prominence.

Increasing visitor numbers and new access routes (e.g., around Krippenstein) risk deeper encroachment of tourism into the landscape. Issues include illegal climbing routes, which are removed when detected, as well as increasing ski touring and snowshoeing. Milder winters may lead to more winter recreational activities in the high plateau nature reserve. The previously advantageous snow closure of roads from Ödensee and Bad Mitterndorf will be less effective with warmer winters. Mountain biking trails are also illegally used at night.

The activities of the Upper Austrian Nature Watch have been professionalized to ensure control, with personnel trained and appointed by the nature conservation authority. Specially trained staff are deployed in areas under high usage pressure.

Despite upward shifts in vegetation zones due to climate change, there are currently no significant invasive species problems, except along riverbanks (e.g., Japanese knotweed). A more pressing issue is the loss of alpine natural and cultural landscapes. Glacier retreat affects the region’s water supply, documented since 1840 by Friedrich Simony. Abandoned alpine pastures overgrow, reducing habitats and grazing areas for species like chamois. Traditional clearing for species such as capercaillie and black grouse is allowed, but controlling the spread of dwarf pines on the Dachstein Plateau is ecologically challenging. Differences in the age of regulations for the Styrian nature reserve and the overlapping European protected area (about 25 years apart) mean the objectives of the two legal frameworks are not fully aligned. The nature reserve emphasizes non-intervention management, whereas the European protected area targets specific species and habitats. This occasionally complicates conservation measures, such as projects for the capercaillie.

A project requiring particular attention is the redevelopment of the former barracks near Gjaidalm into the luxury “Hotel Oberfeld.” The concern is not the reuse of the site itself, but managing recreational use in its surroundings, especially within the nature reserve.

Few caves present usage issues. Some caves have been closed in cooperation with the Federal Forestry Agency, mainly those of high importance for bats. The Dachstein caves, along with Werfen and the Dobšinská Ice Cave in Slovakia, are among the largest ice caves in the world and have long been subjects of scientific research. The Giant Ice Cave has been studied since 1928. Previously managed by the Federal Forestry Agency, the caves were leased to the Krippenstein cable car company, complicating the integration of scientific research into tourist guidance.

Airflow management in the caves has helped maintain ice volume from 1900 to 2000. Recent ice loss due to climate change is currently under study.

A valuable project in the World Heritage buffer zone is the “Inner Salzkammergut Moor Restoration” (e.g., Hornspitz in the Gosau ski area).

In Styria, water management on the karst plateau is of particular concern for sustainable alpine farming. Expert input on karst water management is essential.

The LIFE+ project foresees developing a visitor management concept for the habitats of grouse species (capercaillie, black grouse, hazel grouse, snow grouse) in the Dachstein Plateau and the Totes Gebirge, with follow-up monitoring approximately ten years later. The Styrian nature conservation department would be responsible. The Austrian Federal Forestry Agency continues to monitor reference lek sites and report to hunting authorities, but other species counts are less frequent due to funding, and some species (e.g., owls) remain unrecorded.

The area around Notgasse and Riesgasse in Styria, distant from settlements, is managed to guide visitors through professional tours. The ANISA association in Schladming, specializing in alpine rock art and prehistoric settlements, has conducted research there, uncovering evidence of Bronze Age farming over 3,000 years ago.

Tourism uses such as the Ice Palace near the Dachstein summit in the World Heritage buffer zone generate discussions. Upper Austria shows no interest in further large-scale alpine developments, whereas Styria is more flexible. While activities occur in Styrian nature reserves, they are mostly in the Ramsau reserve, established in 1972 under outdated legislation, and vaguely designated as “plant protection areas.”

Access routes to remote alpine pastures in the strict Styrian Dachstein Plateau nature reserve remain under debate, requiring a balance between strict conservation and the preservation of the high alpine cultural landscape.

In summary, the three main areas of the Dachstein Mountains within the World Heritage core and buffer zones are managed differently:

- Upper Austrian Dachstein Plateau: Upper Austrian Nature Reserve (2018 reissued, permitted uses listed) and European protected area.

- Styrian Dachstein Plateau: Styrian Nature Reserve (1991 issued, prohibited uses listed) and European protected area.

- Dachstein South Wall and Stoderzinken area: Partly Styrian Nature Reserve (1972, based on older legislation) and partly Styrian Landscape Protection Area (first designated 1959, reissued 1997, expanded 2002), without European protected area designation.

It is worth questioning whether ecologically similar units truly require different treatments. Strengthening professional cooperation between Styrian and Upper Austrian conservation staff is recommended for coherent World Heritage site management.

The presence of tourism in the World Heritage area does not in itself constitute a specific value that formed the basis for the inscription of the Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut site on the UNESCO World Heritage List. As with many other World Heritage sites, however, tourism is a central factor in the regional economy of the Inner Salzkammergut, and the World Heritage designation has certainly contributed to local tourism.

Particularly due to the massive increase in visitor numbers over the past 10 to 15 years, tourism in Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut has become the challenge that most strongly affects the World Heritage site and is most closely associated with the site—especially the town of Hallstatt—in public perception.

An efficient and targeted management of tourism is therefore the top priority for preserving the specific values and qualities that have defined and continue to define the Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut World Heritage.

Objective:

Manage tourism in the World Heritage area, particularly in Hallstatt, in a way that is compatible with the values of the World Heritage site, the local population, and the local and regional tourism economy, while making a positive contribution to the region.

Implementation:

The primary responsibility lies with the tourism sector itself. This includes businesses, recreational facilities, tourist transport providers, relevant institutions such as churches and associations, guides, as well as tourism organizations and representation (tourism associations, Chamber of Commerce, specialist groups, and higher-level tourism bodies such as Upper Austria and Styria Tourism).

Important framework conditions are set by all local authorities, particularly the World Heritage municipalities.

The World Heritage Site management plays a central role in coordinating stakeholders and initiating and implementing key projects. All activities of the management require close coordination, especially with regional tourism associations and the World Heritage municipalities.

Tasks for the World Heritage Site management:

- Establishing trustworthy communication regarding the tourist landscape in the World Heritage region. This includes clarifying and transparently communicating the boundaries of the management’s responsibilities, particularly in relation to those of tourism associations. Regular meetings should be held (at least twice a year) or participation in existing discussion rounds within the region’s tourism landscape.

- Integrating key representatives from the regional tourism sector, especially tourism associations, into the advisory board of the World Heritage Site management.

- Initiating, implementing, executing, and evaluating projects that contribute to managing regional tourism. This includes ongoing traffic and visitor counts, surveys of locals, guests, and tourism businesses, and the feedback of these data to municipal and state authorities.

- Supporting project management for specific projects in close coordination with tourism associations and municipalities.

- Addressing and communicating findings and best-practice projects on overtourism. Identifying and, if necessary, initiating networking initiatives on overtourism at both national and international levels, especially with other World Heritage sites affected by similar phenomena.

Even in a living cultural landscape with a relatively small population, such as Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut, the residents of the World Heritage site play a central role in its protection and development. Therefore, knowledge of and commitment to the values and goals of the World Heritage site among locals is crucial for its success. World Heritage education and interpretation are thus central tasks for any World Heritage Site management, regardless of the site.

In a World Heritage site strongly dominated by tourism, such as Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut, providing information and interpreting the values and content of the World Heritage site to visitors is equally important.

In line with the concept of an “expanded World Heritage region” including buffer zone municipalities, measures for World Heritage interpretation refer to this larger regional context.

Objective:

Sustainably develop awareness-raising and interpretation programs on the goals and values of the World Heritage site for both locals and visitors.

Implementation:

- Embedding the values and goals of the World Heritage site in the educational programs of kindergartens and schools in the region is crucial to establish awareness of the World Heritage site among children and youth at an early stage. Some schools have already distinguished themselves in this regard (UNESCO and World Heritage schools).

- Regional print and online media, as well as local radio stations, serve as important multipliers for raising positive awareness of the World Heritage site.

- Coordinating programs for children and youth, and developing programs for adult locals and visitors in cooperation with churches, associations, and other key actors and multipliers, is a central task of the World Heritage Site management.

Tasks for the World Heritage Site management:

- Establishing trustworthy communication with educational and research institutions in the region, including regular meetings (at least 1–2 times per year). Integrating key representatives of the regional education sector into the advisory board of the World Heritage Site management.

- Building trustworthy communication with regional media.

- Designing an integrated overall concept for awareness-raising and interpretation activities and regularly monitoring how well World Heritage awareness is embedded in the region. This project is a top priority in implementing the management plan.

- Coordinating awareness-raising and interpretation programs for local children, youth, adults, and tourism multipliers in the World Heritage region.

- Discussing and coordinating decisions regarding the establishment of a World Heritage visitor and competence center in the region. If such a center is established, managing the entire project from planning and construction to operation.

Aside from issues related to the extent of tourism, questions of quality of life in the World Heritage area are generally of central importance for the positive future of a living cultural landscape, which depends largely on the initiative and positive attitude of the local population toward the World Heritage.

This must be seen in the context that the Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut World Heritage region is an extremely peripheral area, which has been heavily affected by regional structural changes and associated population decline over the past half-century, and to some extent continues to be.

Objective:

Improve or at least stabilize key factors affecting the quality of life of locals in the World Heritage region, such as the regional labor market, sustainable public transport connections, and the availability of affordable building plots and housing.

Implementation:

The primary responsibility for these areas lies with the municipalities (housing, public transport), regional businesses (labor market), and other important stakeholders such as transport providers (public transport).

Tasks for the World Heritage Site management:

- Establish trustworthy communication with regional businesses, holding regular meetings (at least once a year) or participating in existing discussion rounds. Integrate key representatives of the regional economy into the advisory board of the World Heritage Site management.

- Support regular schedule dialogues between public transport providers and municipalities.

- Monitor and, if necessary, address the quality of the connection between Hallstatt and the train station, and, if needed, support the enhancement and maintenance of the station area and station building.

The Inner Salzkammergut is also affected by the impacts of climate change. As in other inner-alpine regions, the focus is particularly on mitigating natural hazards. Even in a World Heritage region, considerations should be made regarding how the region can contribute, within its means, to managing the effects of climate change and to restructuring the energy system.

Objective:

Actively engage with the possibilities for the World Heritage region to contribute to managing the impacts of climate change.

Implementation:

- Mitigation of natural hazards through planning projects for torrent and avalanche control by municipalities, taking into account archaeological and nature conservation interests, in cooperation with institutions such as the Austrian Torrent and Avalanche Control and major land managers (e.g., Austrian Federal Forests).

- Continuous optimization of disaster management plans and strengthening/support of volunteer organizations.

- Awareness-raising and small-scale projects through the KLAR! region and, according to future Leader strategies (mandatory fourth thematic field), through the Leader regions.

World Heritage Site and Buffer Zone

World Heritage Site

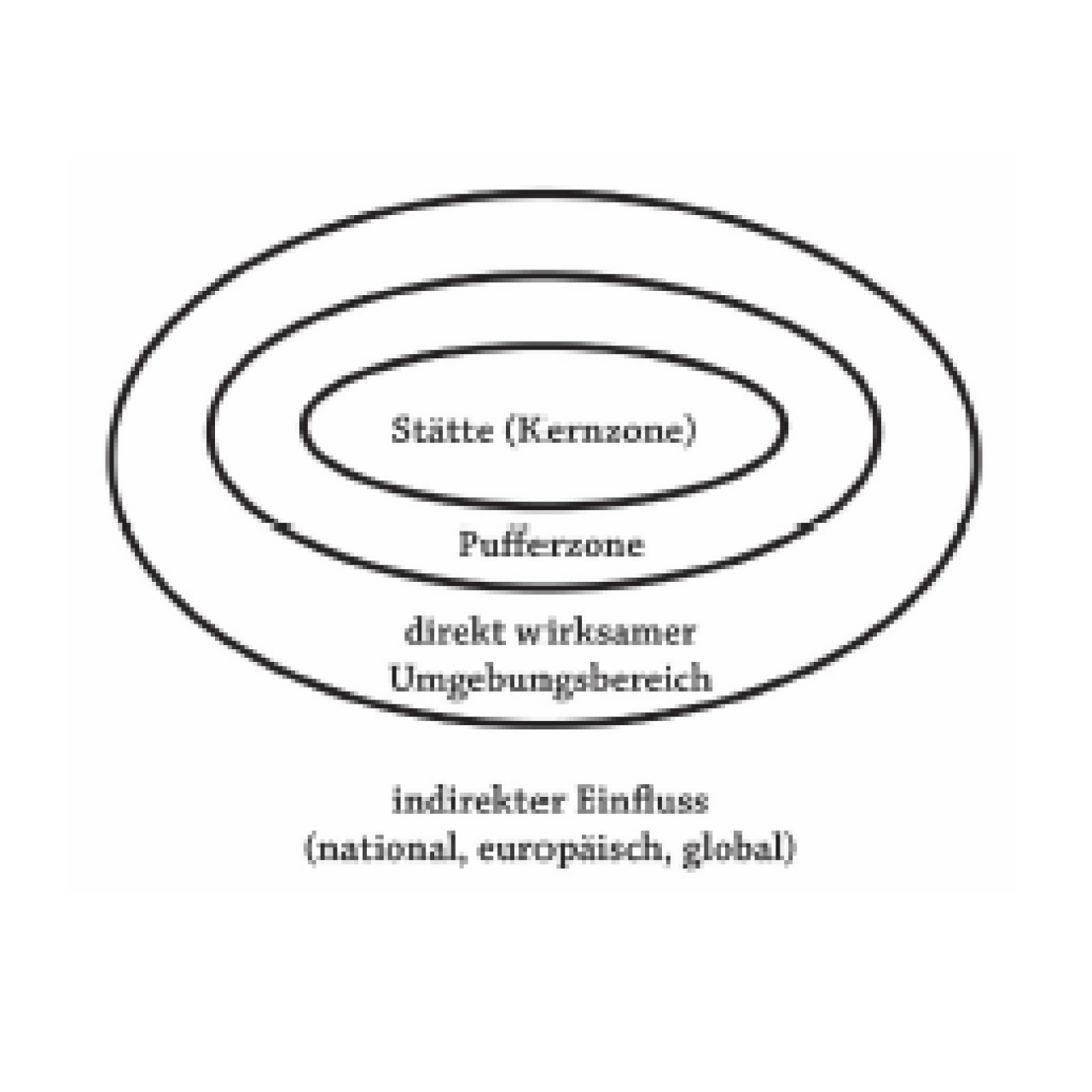

The Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut Cultural Landscape is defined by a core area. The term “core area” is no longer officially used; only the term “World Heritage” is applied, to make clear that the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) applies exclusively within this area. It is important to understand that all elements, features, and attributes that define the site’s value must be located within this zone.

Buffer Zone

The buffer zone functions similarly to the surrounding protection of monuments, providing an extended geographic area intended to prevent changes there from diminishing the World Heritage site itself (the former core area) or its associated values. The buffer zone is not part of the World Heritage, but it plays a decisive role in its protection. For example, the view of Hallstatt from the lake is a key element; any major changes in the buffer zone that would diminish this view are therefore not permitted.

World Heritage and Architectural Culture

High-quality architectural culture enhances quality of life and strengthens the economic value of the Salzkammergut region. Achieving this requires balancing various aspects in the maintenance and operation of buildings as well as in the development and implementation of new projects—above all, functionality and beauty, durability and cost-effectiveness.

Architectural culture concerns everyone: it succeeds wherever people design their living environment with high standards. It includes buildings and settlements, towns and villages, landscapes, roads, and utility structures, and is connected to land use planning and architecture, spatial planning and regional policy, the economy, and infrastructure. Where architectural culture is of a high standard, we perceive the built environment as livable and feel comfortable in these places. When architectural culture is neglected in project planning and implementation, urban sprawl and asphalt landscapes expand, town centers decline, and inhospitable spaces develop where people do not want to spend time.

For the future development of architectural culture, it is important that:

- Awareness of architectural culture is cultivated and suitable structures are promoted.

- The public good is strengthened.

- Planning is holistic, long-term, and innovative.

- Land and other resources are used wisely.

- Public funds are tied to quality criteria.

More information at www.baukultur.gv.at